Republicans Have Reason for Optimism in the Nevada Senate Race

An in-depth dive into Nevada's hotly contested 2022 senate race.

For most of its existence, Nevada was an empty, arid desert, with a few small towns located in the North. At the dawn of the 20th century, Reno and Carson City both had populations under 10,000, while Las Vegas was a dusty, unincorporated area in the southern extremity of the state with a population of 25.

The state had been incorporated as a Union state and favored Republicans, but it also had a populist streak. William Jennings Bryan won over 80% of the vote here and carried it each time he ran. During the New Deal, it was also overwhelmingly Democratic: Franklin Roosevelt won over 70% of the vote in 1936.

But political alignments shift. By 1944, the state was voting roughly at the national average, with FDR defeating Republican Tom Dewey by a little bit more than his national average. By the 1960s, reaction toward the federal government’s management of public lands, the burgeoning environmental movement, and some of the social movements gaining steam nationally had propelled the state toward a solid Republican lean. By the 1980s, the state was overwhelmingly to the right of the country as a whole.

The state’s rightward lurch eventually came to the Senate delegation, with Senator Howard Cannon losing to Republican Chic Hecht in 1982, while Democrat Alan Bible retired in 1974 and saw Paul Laxalt take his place despite the strong anti-Republican mood that year. Laxalt retired after just two terms, and was replaced by Rep. Harry Reid, who would rise to the rank of Senate majority leader during the Obama years. Reid himself retired in 2016 and was replaced by another Democrat, former Attorney General Catherine Cortez Masto.

While all of this was taking place, the state had moved substantially toward Democrats. The line chart above shows how the state voted in presidential elections from 1968 to 2020, compared to the national average. That is, if the country gives the Republican candidate 55% of the vote nationally but she wins Nevada with just 53%, the state is considered two points to the left of the country.

As you can see, by 2004 the state was roughly where the country was overall after steadily trending leftward. In 2008, it lurched even further leftward, as Barack Obama won the state – which was then ground zero for the subprime mortgage meltdown – by double digits.

Yet since then, the Democratic edge in the state has retreated. By 2016, it was back at the national average. In 2020, propelled by a surge in working class and Hispanic support, it was to the right of the national average by a couple of points, which reflected the best Republican showing in the state since 2000.

This is the backdrop against which former Attorney General Adam Laxalt, the grandson of Paul Laxalt and son of Sen. Pete Domenici, finds himself as he seeks to reclaim his grandfather’s seat. The state has moved rightward of late, and his opponent, Catherine Cortez Masto, has had an unspectacular first term. The Democratic president is grossly unpopular in the state, with multiple polls finding his job approval in the 30s, and she has not cracked 44% in a poll this year.

This is the rare Senate seat this cycle where Republicans landed a top recruit; in fact, Laxalt came just four points from winning the governor’s race in the otherwise atrocious Republican year of 2018. Absent a major shakeup to the political environment, he should be well positioned to win.

What is going to decide the race? To understand this, let’s start with a map of Nevada, showing the results of the 2020 presidential election by county:

Looking at this map, you would think the state was pretty red. While the county holding Reno (Washoe) and the county containing Las Vegas (Clark) are purplish blue, the rest of the state is pretty red.

The issue becomes clear, however, if we resize the counties by their population:

Nevada is effectively a city-state, with almost 80% of the vote being cast in Clark County. Another 10% or so comes from Washoe County. In other words, while those rural areas do cast a lot of votes, and those votes are almost entirely for Republicans (the optimistically named Eureka County gave Biden just 10% of its votes), they’re eclipsed by Clark County. To emphasize: In a close race, those votes matter, but to get to a close race, the action is in Clark.

Zooming in we once again see a whole lot of red. But again, many of those precincts are lightly populated. Las Vegas really is an oasis in the desert, and once you get outside of it, the area quickly turns very rural, very quickly. (Note: I’ve truncated the vote share at 40% Biden and 60% Biden for purposes of the maps, because allowing the color scale to range from 0 to 100 washes out the crucial 40% to 60% range in a sea of undifferentiated purple).

So to really understand the political dynamics of the state, we should zoom in even further, to the Las Vegas metro area:

Now we see the strength of the Democratic coalition in Nevada: centered in Las Vegas and North Las Vegas, with pockets spread throughout the metro area. How does Laxalt get to 50% plus one?

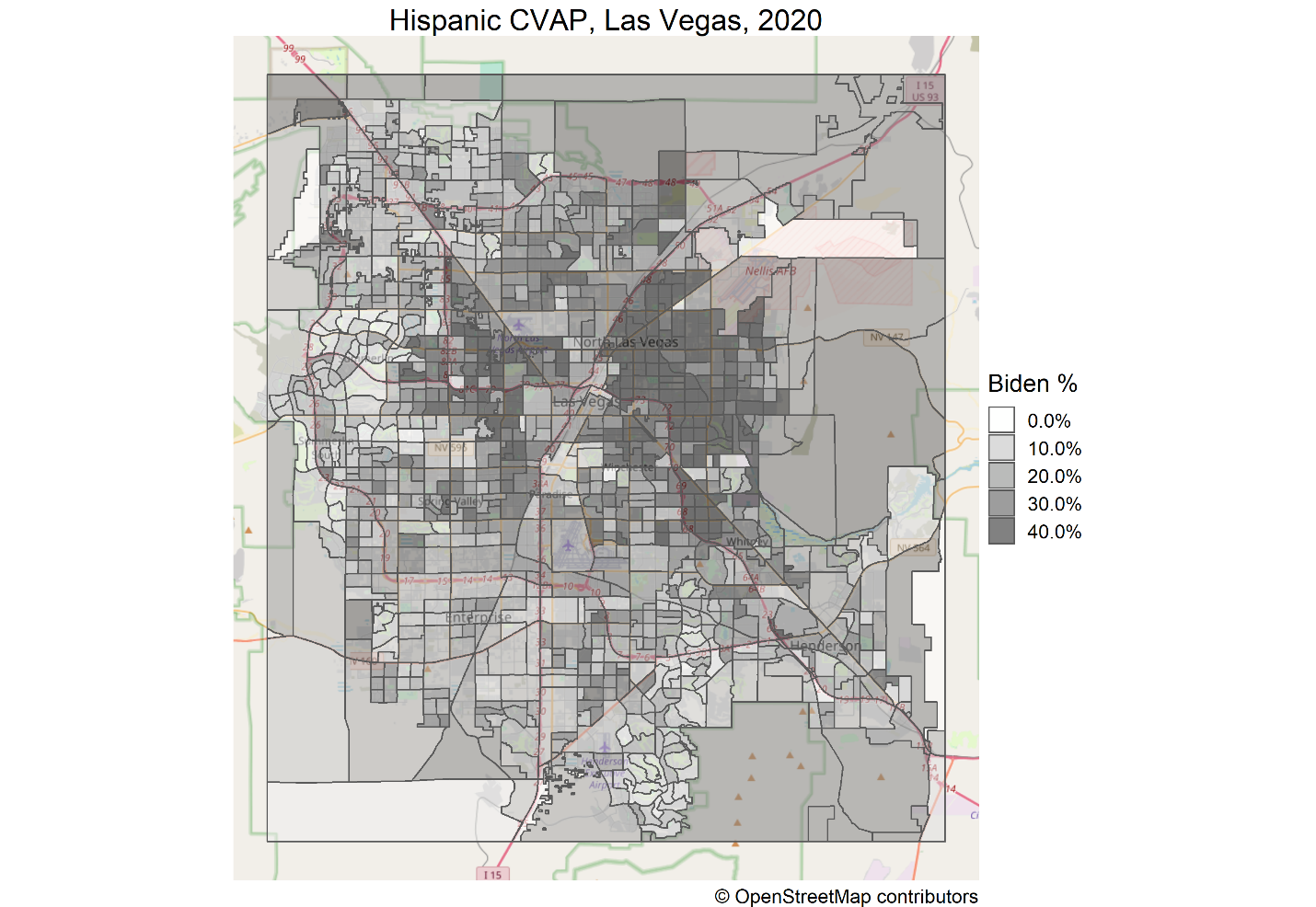

The key can be found in two more maps. The following shows the Hispanic citizen voting age population (CVAP) of Las Vegas by precinct. As you can see, the Hispanic population is concentrated in a bowtie shape centered on downtown Vegas. Those areas are solidly blue in our map.

But although these areas are blue, they nevertheless saw a sea change in their voting patterns. Looking at the change in vote share from 2016 to 2020, we can see that these areas tended to have a red hue to them, as blue collar areas like Sunrise Manor and Paradise saw Trump’s vote share improve by three points overall, even as the rest of the country was moving away from him. Heavily minority North Las Vegas likewise lurched toward Trump (although Biden still won it handily).

At the same time, wealthier suburbs like Henderson and Summerlin moved away from Trump, as a part of the general national trend away from the GOP in 2020.

So how does Laxalt win? First, he has to count on the trends among Hispanic and blue collar white voters to continue to be at least as strong as they were in 2020. Another round of improvement among these groups would certainly go a long way toward helping him win the election. At the same time, Laxalt has to hope his establishment credibility helps him in the suburbs. In 2018, he ran as well in Henderson and Summerlin as Trump did in 2020, despite the toxic 2018 environment, so he has reason for optimism now that the fundamentals are running strongly against Democrats.

None of these things will be easy, but they’re also far from insurmountable. This remains the GOP’s best pickup opportunity this cycle; if they lose here, it will probably have been a very, very disappointing night for them.

Sean Trende is senior elections analyst for RealClearPolitics. He is a co-author of the 2014 Almanac of American Politics and author of The Lost Majority. He can be reached at strende@realclearpolitics.com. Follow him on Twitter @SeanTrende.

And who counts the votes?

I like how they say the country was moving away from Trump, yet he gained 12 million more votes.